An Accidental Tenebrism in the Woods

Bats, ecology work, and the art of Joseph Wright of Derby - an extract from a work-in-progress

The controversial Norwich Western Link Road is planned to crash through these woodlands, taking a swathe of habitat with it.

The camping table sits next to the woodland track. It has been carefully laid out with scales, lights, a small bone measure, pens, and a plastic covered clipboard. Nearby a Dacia Duster has its boot raised to reveal more equipment. The wood has become a laboratory of sorts. Such is the world of conservation science. It is summer 2024, and I am in the woods with a team of conservation scientists led by Dr Charlotte Packman, who has been surveying the bats that live in our woodland for the last five years. Lotty is here to carry out a radiotracking survey, and although I’ve observed this before, I wanted to watch it again in case this was the last time the survey would be carried out. The controversial Norwich Western Link Road is planned to crash through these woodlands, taking a swathe of habitat with it, and the planning consultation is live, the deadline only days away. Despite opposition from a coalition of wildlife organisations led by Norfolk Wildlife Trust, and despite Natural England, the government advisory body on nature, casting doubt on the ability of the developers to mitigate for the impact on the rare Barbastelle Bat colony that lives in these woods, Norfolk County Council have pressed on with the proposals. If it gets through planning, then next summer we might be standing amidst earth movers and tree felling machines rather than the mature oaks and Douglas firs that tower in the darkness around us. Another of the woodland owners is here, and Cecilia, my wife. We sit on camping chairs with headtorches and masks to hand.

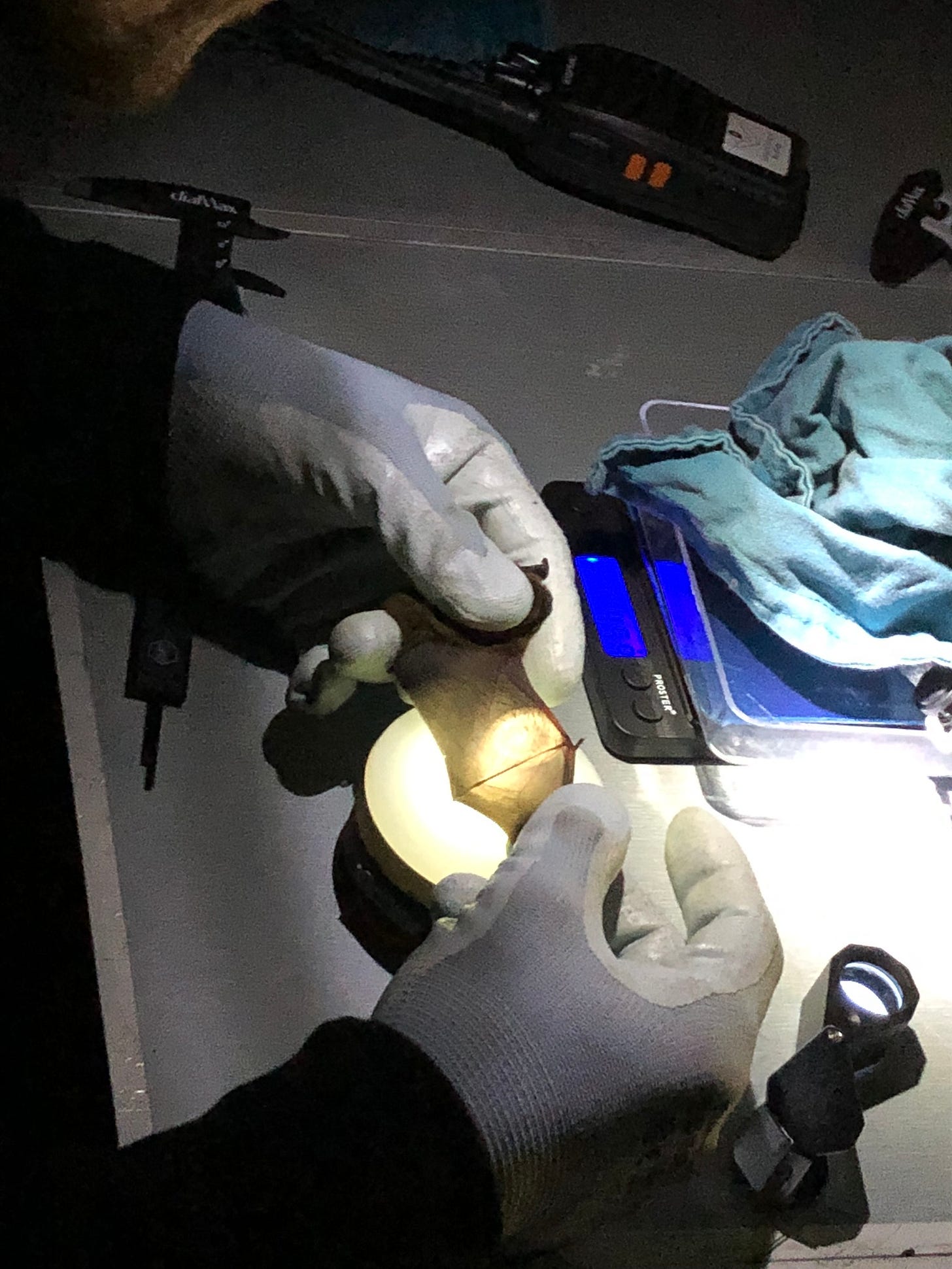

Dusk has been coming on fast and the first few bats have been caught in the fine mesh nets that have been expertly strung across the known flight paths. Bats tend to prefer linear features to navigate, following the edges of woodlands or hedgerows, or in this case, the ride that runs through the woods towards the wet pastures and feeding grounds of the hungry winged mammals. These bats are soprano pipistrelles, who are often the first to depart their roosts. Ecologists and observers alike mask up, more to protect the bat from diseases we might carry than the other way around. Each bat, no matter which species, is carefully weighed, measured, and examined for its sex and to determine whether, if female, it is lactating and has therefore bred this season. Lotty demonstrates the way to differentiate the soprano from the common pipistrelle, a faintest of differences in the veins in the wing, to her student volunteer, gently extending the bat’s wing over a small camping light to illuminate the pink membrane. As its name suggests, the soprano also calls in a higher frequency range of 52-55 kHz. The bats are kept in cloth bags to minimise stress until they are examined and then released. The next round of net inspections brings more pipistrelles and the Natterers bat, my personal favourite for its gingery fur and slightly goofball expression. A 2021 roost tree survey carried out by the developers identified the roosts of at least eight different species in the trees in these woods, a presence which is confirmed by the acoustic surveys carried out by Lotty’s team, but it is the barbastelle bat that is generally regarded as the most important of these and which is the focus her long-term study in this area. This species is considered near-threatened with extinction and is not in what Natural England calls a favourable conservation status. It seems to thrive in long-established and ancient woodlands, where older trees with splits and loose bark make ideal roost trees for their colonies. Such old-growth woodland is a habitat which is in decline. The woodland we are in is an old estate woodland, a mix of ancient and planted, but largely unmanaged, with broken and dead trees often allowed to remain in situ. Most of us woodies are all too aware that this makes for great habitat for all sort of creatures, and so trees are only felled or removed when they pose a danger of some kind. The nearby River Wensum provides the sort of wet pastures, and with it, insect life, that enables rich foraging for the bats. These elements coupled with the lack of development, noise, and artificial light make these woodlands special for the barbastelle.

Bat survey in 2019.

…the ecologists working methodically, the light pooling on the camping table that is their workstation, the woods greying into a blackness that feels more definite and solid than any darkness experienced outside of the trees.

It is the fourth trapping I have attended, and each time I’ve been struck by the strangeness of the spectacle, the ecologists working methodically, the light pooling on the camping table that is their workstation, the woods greying into a blackness that feels more definite and solid than any darkness experienced outside of the trees. The contrast between the bright torch light, the clinical white LED, and the darkness that seems to swallow the light, contain it like an island in a vast ocean of night, is reminiscent of something that I struggle to name. Perhaps it is that instinctual genetic memory of firelight in the wild, or the safety of the hearth, fire that promethean gift that separates us from all other animals, that equation of light with knowledge.

A kestrel was calling incessantly as dusk came on. I realise that it has fallen silent, no doubt nestled somewhere in the dark jumble of branches. This wood is good for birdlife. Kites and hobbies are often seen or heard. There are even nationally rare honey buzzards in the area. By the time the Natterer’s bat is being recorded the owls are emerging, first the loud shriek of a barn owl resounding from the meadow that is fated to become a cutting for the new road, and then the night-long chatter of the tawnies, calling and replying through the trees. It isn’t until a third sweep of the nets that a barbastelle is trapped, and we are in luck - it is a female and lactating. This means that the bat can be radio tagged with a small transmitter and then tracked to its maternity roost. The roost can then be observed at dusk and the occupants counted as they leave. This gives a sense of the overall size of the colony and by comparing this to previous years Lotty can gain a picture of its overall health.

The gluing of the radio transmitter to the female bat is meticulous work. The transmitters have been miniaturised so that they are in the middle ground between a pea and a pinhead, with a thin and flexible antenna, to make them weigh as little as possible. Such tiny perfection comes at a price, which each transmitter costing well over a hundred pounds. The idea is to glue it to the bat’s back, between its shoulders, in a spot guaranteed not to impede movement or flight.

It would weigh no more than a light backpack might on us, explains Lotty. She is demonstrating each step of the process to her student volunteer, whose role in the procedure is to hold open the glue pot at the right time and angle. The transmitter is turned on and tested, its chirruping signal strong through the tracking equipment, and then the gluing can begin. First Lotty must comb a parting in the dense black-brown fur of the bat, teasing it apart until a line of skin becomes visible. The bat is held against a soft rolled up cloth during the process, more comfortable for the bat, though it’s difficult to know how they must perceive what is happening to them. Angry bat chatter resonates from the iPad, picked up by the acoustic detector plugged into it. Lotty expertly handles a pair of scissors to remove the fur in the areas where the transmitter is to be glued. This bat, like any of the others caught by her team, is treated with care and respect. This is a wild creature, and everything is done to minimise the time it is captive, but Lotty also needs to be sure that the glue will hold. There is an air of quiet concentration, and I feel as if I’m witnessing a medical procedure of some kind on the tiniest of patients. The work is carried out under the glare of head torches, pooling a circle in the blackness around us. I look up at the dark and silent canopy of the trees, oaks and Douglas firs, high above us, and around at the deep oblivion of the night wood. The scene at the table, I realise, is something like that of Joseph Wright of Derby’s enlightenment oil paintings, the sharp contrast between dark and light, an accidental tenebrism, with LED bulbs rather than candles, and the furtherment of knowledge and science at the heart of the light, the figures bent around it, Lotty and her team, as if in devout reverence.

Once the fur is trimmed a small amount of glue is applied to the skin of the bat, and then some to the transmitter, and when tacky enough they are bonded together, and the fur combed back over the spot. The glue is designed to dissolve over time, and the transmitter will eventually detach and fall off. Getting the timing right is key, the bond must be strong enough to allow for Lotty’s team to gather about ten days of data, after which the battery will start to fade. If the bond is too weak, the transmitter might drop off too soon and the opportunity would be lost. The bat is kept until the glue has hardened, and then released, fluttering briefly and dramatically in our head torches, the chirrup of the transmitter diminishing as its hunting instincts kick in and it flies towards its foraging grounds in the wet woodlands and pastures of the Wensum.

The scene is framed by shadows, but the focus of the light is on two young girls, one of whom shields her face in distress, while the other, the younger, watches the suffocation of the bird with a horrified scientific curiosity.

It is getting late, and Cecilia and I pack up our camping chairs to leave. Lotty and her team work on. I know they will want to catch and tag at least one more female barbastelle and will potentially not pack up until the small hours. My fellow woodland owner stays to make a night of it, his camper van parked up nearby. I cast a look over my shoulder as we leave. That scene again. Joseph Wright of Derby. Two of his most famous paintings depict scientific demonstrations. In ‘An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump’ (1768) a group of well-dressed observers are watching a wild-eyed man with a mane of long grey hair as he operates an air pump on a bell jar containing a cockatoo. The bird’s empty cage hangs darkly in the background. The scene is framed by shadows, but the focus of the light is on two young girls, one of whom shields her face in distress, while the other, the younger, watches the suffocation of the bird with a horrified scientific curiosity. Of course, there is no such horror in the bat survey, only the scientific curiosity, and the desire to look fully into the well lit scene. I think of our own teenaged daughters, neither one here tonight, and of what they are missing. The other painting, ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’ (1766), again places the faces of children at the radiant centre of the composition. Two boys gaze with rapt fascination, intent on the mechanism before them, as a philosopher explains and demonstrates the movements of the planets and moons. This scene is also framed by a deep darkness, as vast as the night stretching beyond the pooled light of our headtorches as we tread our way along the woodland ride. The technique is taken in part from Caravaggio, but Joseph Wright, instead of painting a Saint at the focus of the light, chose to depict knowledge and learning at the illuminated heart of his scenes.

Joseph Wright of Derby, ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’ (1766)

Only one bat is tagged that night. It is one that had been trapped before, and ringed, in our small area of woodland by the consultants working for the road project team three years earlier. That it could be trapped again so close to the original trapping location shows how site loyal these mammals are, returning year after year to the same selection of trees in their home woodlands. The idea perpetuated by some ignorant corners of the pro-road building camp that bats and other wildlife will just move on is inaccurate misinformation, especially for this species. Their requirements for habitat seem to be exacting, they won’t just roost in any old tree, and they seem to prefer the familiar safety of certain trees in which to breed and nurture their young. Lotty messages me the following day to say that she’s tracked the colony back to the first tree she identified in our woods as a roost tree, five years ago. The count is good, perhaps more breeding females, and it’s possible not all the pups have yet flown. The days that follow will reveal more, each dusk bringing new clarity. I think back to the table in the wood, the pool of light, full of promethean promise, knowledge, enlightenment as an ongoing process, held in the eyes of the future.

Iain- I love Wright's work and the point on focusing light on education, learning, curiosity, and wonder. I appreciate this. Hope you're well this week? Cheers, -Thalia

What are the chances now of stopping the road do you think? It's always heartbreaking to see beautiful woodland or other habitat destroyed for roads and other infrastructure.