20/10

We set out for a walk after the storm has passed with just an hour of daylight left, then head up to the ‘the top’. In the former corn field we see three roe deer, their white bobble-tails dancing as they flee to the hedge. A dark arm of blue-grey cloud retreats to the north and as it does the light lifts even as the sun falls. The mackerel skies that the storm has left in its wake begin to light up silver then coral. By the time we are walking back along the lanes the sun has set and the residual light feels immense, refracting off every gaseous surface in the sky as the road falls into dusk.

21/10

We get home and change into wellies. The clocks go back soon, which means we won’t be able to walk in daylight after work for much longer, and getting out will be a negotiation around schedules. Off the lanes we spot two muntjac through the gaps in a hedge, seemingly playing, relaxed, in a freshly mown paddock. We watch them for sometime, turning and running, sniffing each other. One lies down, before leaping up again and chasing in a circle. Muntjac breed all year round, with a long 210 day gestation, so I wonder if this is a precursor to mating. Finally, one notices the shape of me, and sniffs the air, wary. I remain still and it relaxes, grazing on the hedge. We watch a little longer before moving further along the lanes and up past the old farmhouse.

The sky is dull with cloud and the fields look muck-brown as we trudge up the churned up track to the top. On the way back the sun suddenly appears on the horizon like an egg yolk and the ash saplings and oak trees in the hedgerows are gilded with its light. The clouds begins to glow peach and rose. By the time we turn out of the lanes towards the village the eastern horizon has grown orange as if the whole of it was ablaze.

24/10

In the late afternoon I drive to Norwich with my daughters, leaving them for half-term roaming while I deliver a brief address during the opening drinks reception of the Norwich Book Festival. It is dark by the time we get back and I realise that I’ve barely noticed anything beyond my screens all day, no time for walking or even a brief wander in the garden.

25/10

I spend the morning writing emails and marking-up manuscripts. We have no bread, and neither of us feel like baking it, so I set off for the Co-Op in the nearest big village, forgetting that the road between our villages is for some reason closed. I detour through a third village, passing the vast excavations of the cable installation. The temporary road surfaces for the heavy vehicles look very permanent, the track dug into the side of a rare Norfolk hill, and it is difficult to image how they will restore the land here. Wherever the cable route goes, new or existing field entrances have been widened and tarmacked, post and rail fencing installed, as if in preparation for development. I enter the large village through one of its new, under-construction, estates, and I’m momentarily disorientated, because the last time I took this road it was still fields. The suburbia begins abruptly and is uncompromisingly bleak in its intensive land use and unimaginative architecture. Persimmons. Taylor Wimpey. All the usual culprits seem to have a slice of the action, naming the new cul-de-sacs after vanished rural handicrafts and trades, or red-listed species. Houses stand in various stages of half-finished in what feels like an assembly line of homes. Flags flutter on the lawns of show homes.

Benji, our older cat, comes to the door with a small dead rat, which he doesn’t eat. It is light grey with a thick tail and large pink feet. It looks too small to be fully adult and must have been born this year, which means there will be more around. I dispose of it in the field ditch where its nutrients will be recycled in one way or another.

It is a warm afternoon after a week of foggy mornings and weak sunshine. We peel off layers as we walk up the lanes. All but the highest blackberries are gone. Long tailed tits flash and barrel between the crowns of the hedge oaks. In the sticky mud of the track up to the top we find the remains of hawthorn berries, split and half-eaten, perhaps by the crazy flock of linnets that darts and wheels around the hedgerows here. Ceci gathers a pocketful of rosehips. I show my eldest daughter the rapeseed heads in the regeneratively planted cover crops, of how the pods split to reveal the small black seed, and we walk for some time along my favourite hedge splitting the seed heads. The sound of the traffic on the nearby road falls away as we cross the wooden footbridge over the field ditch, and all we can hear is our own foot-crunch and the call of a buzzard. The cover crop left on one of the lower fields has chicory, rapeseed, and some sort of brassica which we can’t identify, but which looks edible. On one of these cabbage-like plants we find a mass of what I think are large white butterfly caterpillars at work, munching side by side.

26/10

Not long after midnight a fox is barking with such volume and persistence that I go out with a torch to check on the hens. The bark is too sharp and high to be a muntjac. It is coming from the far end of the copse that borders our garden. A mist is beginning to pool in the mild night and the torch makes milky beams. The hens are secure but the cats are excited and wild looking when I come back in.

27/10

The clocks have gone back, the short days are here and there are still seven weeks or so before the darkest. I work a little in the morning, and then after Sunday lunch we set out on our annual chestnut foraging trip to the woods. Our little patch of woodland has an acre planted up with sweet chestnut trees, but timing the visit so that it coincides with the best nuts having fallen, and dry stable weather, is never easy. If it rains too much the chestnuts become mouldy once we get them home. We are also in a race against the squirrels for the best nuts. Really we should visit every weekend in October, but work and Covid have interrupted that plan (as they did last year).

On the track we pass a tall beech tree that died a few winters ago. It keeps dropping its branches dramatically and is covered on one side of its trunk by some sort of bracket mushroom, as its rotting wood is slowly recycled. Ivy is overtaking it. One day it will collapse completely, but for now it houses bats and beetles, and a world of unseen fungal biochemistry.

A friend has told me about the remains of a campfire and excavations in an area of designated ancient woodland on the track up to our patch. I check it out, and although the fallen leaves have disguised it somewhat, I find the area of burning easily. It is probably wild campers, with the dug pits being latrines dug just in case. It wouldn’t matter if they’d chosen another less sensitive patch of woodland (there is a conifer plantation right next to it) , but this is an ancient bluebell wood, and it’s likely they will have disturbed and destroyed bulbs in the digging and burning of the fragile woodland soils. Ancient woods are nothing without the soils that take centuries to develop, so it’s important to keep disturbance to a minimum. I like wild camping myself (or at least the idea of it—the reality is usually pretty uncomfortable) and I’m not unsympathetic to the right to roam but there seem to be too many people out there who don’t have the first idea of the damage they can do if they don’t choose an appropriate site.

In the chestnut woods we don gardening gloves for the spikes of the outer case of the chestnuts and set about looking for ones that haven’t already split open. Leaves patter down around us like raindrops. There are mushrooms of various sorts growing everywhere, an indicator that the biodiversity of this wood, which sits on the age of the Wensum flood plain. Not for the first time I find myself wishing I knew how to identify mushrooms. Beyond the chanterelle, which doesn’t grow in our wood, I’m at a loss. Today, our eldest realises wistfully, is the last ‘chestnut day’ before she goes to university. ‘My frontal lobes must be developing’, she says, ‘because I find this fun now.’ She is holding the cases in both hands and peeling back the skin, before depositing her finds in the carrier bag I have on my arm. I’m using a flint tool I found several years ago to split open the cases. Palm-sized, it is ideal for the job, even though there were probably no chestnut trees in England when it was made in the early iron age. It has two blades, one curved and one concave, with two sharp points, which I use to pry open the spiny cases. Our younger daughter still finds the chestnuts boring, but is happy in the bright autumn light.

There is something primal about foraging that connects us with our hunter-gatherer past. Some genetic muscle memory, some deeply felt endorphin rush, seems to come with such activities. I have no research to back this up, but anyone who has picked mushrooms, collected berries, or gathered nuts will know this feeling. I’ve just been teaching Russell Hoban’s unique and influential novel, Riddley Walker. Published in 1980, it describes a future England in the grip of a long post-apocalyptic recovery. Thousands of years have passed since the ‘bad times’, and the only clues as to what has happened in their dark past lie in the fossil language they speak, an English peppered with the relics of a technological past, and in their folkloric stories and officially sanctioned puppet shows. Riddley belongs to a hunter-gatherer tribe whose traditional lands are becoming fenced in, enclosed, and with this enclosure their foraging rights, their right to roam and wild camp, are becoming limited, The entire book is written in a future dialect, in Riddleyspeak, so to enter the novel is to enter a linguistic worldview which is, itself, a riddle. Property ownership and scientific discovery are shown to go hand in hand with the ‘clevverness’ that resulted in the ‘one-big-one’ and the fall of mankind. It is a remarkably complex novel that fuses Greek myth with the stories of Christian saints, particle physics, and indigenous pre-Christian iconography. In any case, I have Riddley in mind as I gather chestnuts on the first day of Greenwich Mean Time.

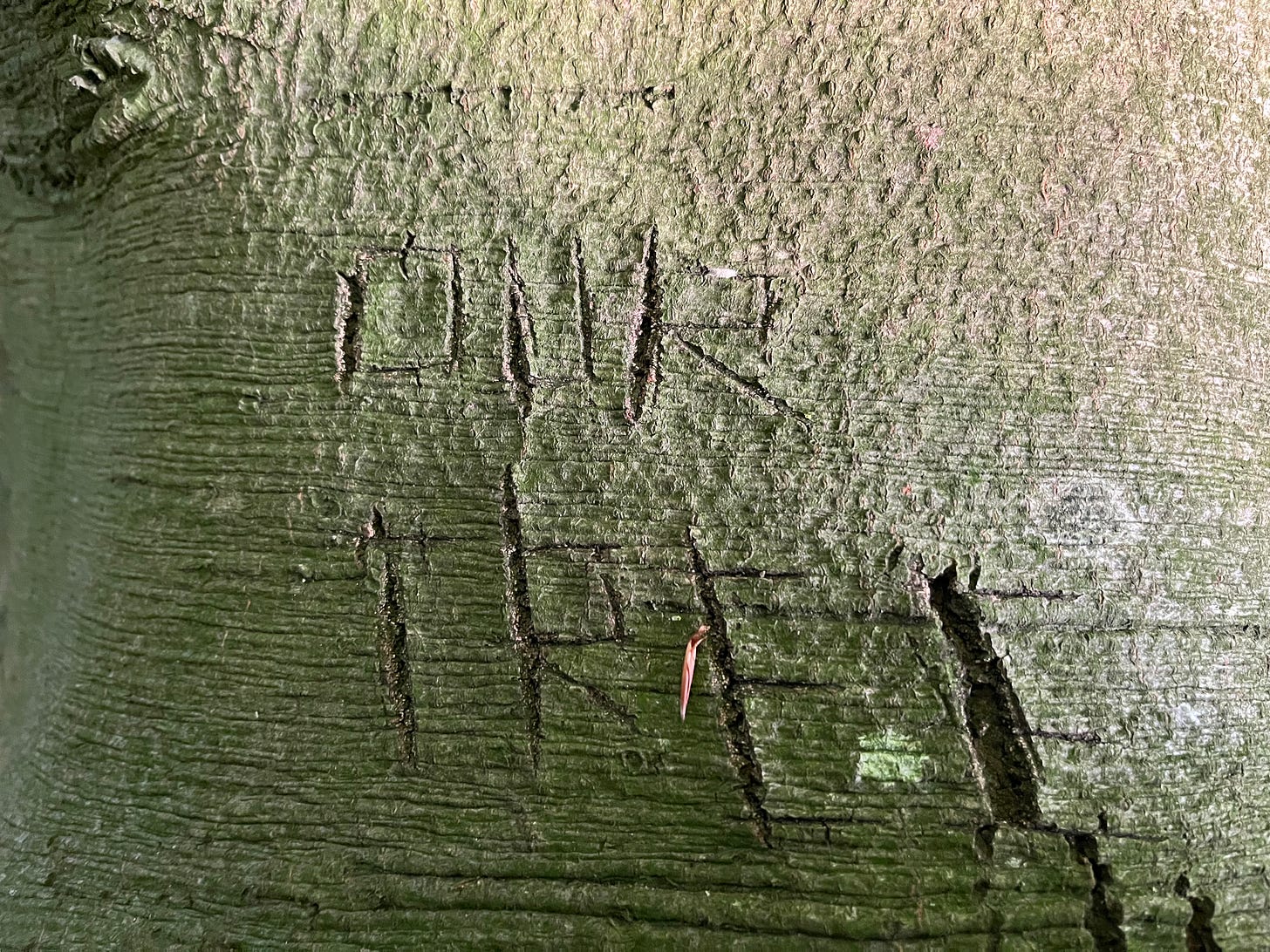

We’ve been fighting to save our little patch of woodland from road development for the best part of six years. Our daughters have grown in that time, but when they were younger that fight coalesced for them around their favourite climbing tree, a youngish beech tree with a solid spread of branches for them to hoist themselves with their books into reading spots high enough to feel like they were beyond adult control. The plight of this tree felt for them more comprehensible in scale than that of the whole woodland and the surrounding area. Before we leave we visit the climbing tree and find the carved initials of all the friends they’ve taken there, and this mark of ownership— OUR TREE.

By the time we walk back down the track, the sun is casting golden stripes across the thickening leaf debris on the woodland floor. Its light flickers between the trunks and branches, in and out of sight. We can smell wood smoke from one of our woodland neighbours who seem to have friends visiting for the day. Close your eyes and you’re in Riddley’s world, or the world of the hands who made my flint tool. Open them. There’s a glimpse of a hare running into cover. The sound of a deer crashing unseen in the undergrowth.

The country diary can express a sort of local distinctiveness, explore a personal set of interactions with a landscape, and in doing so, almost accidentally, tease out the way the natural world is entwined with culture and politics. It can be a quietly radical and uncanny form, or sometimes just plain parochial, oddball in its specificity.

You can read the previous instalment here:

If you enjoyed this post, please consider clicking the 'heart' icon below, or restack the page to inform others (and the algorithms), as it will help in increasing the visibility of my writing. Thank you!